"History, literature, and the passing scene"

Guy Vanderhaeghe reflects on his new book and the shifting world of publishing

In this space, I recently wrote about my plan to attend a book launch for celebrated author Guy Vanderhaeghe. Before the event, I lurked among the bookshelves until I tracked him down and asked if I could trouble him for a subsequent interview.

He said yes.

Take it from me. When you get access to Vanderhaeghe, you are guaranteed fascinating tales and you make that interview last as long as you can.

He is not just one of Canada’s most decorated authors but also a historian — in the general sense, but also of the literary scene. So when he answered my questions about publishing, and how and why it has changed so drastically (and unhappily) over the past many years, I listened even more intently — raptly, really — than I usually do.

Which is saying something.

First, an introduction.

When Guy Vanderhaeghe published his first major work in 1982, he made a dramatic entrance onto the literary stage.

Man Descending, a collection of short stories, won the Governor General’s Award for English fiction — the most prestigious Canadian literature award (although the Giller Prize purse is larger) — and subsequently also took the United Kingdom’s Faber Prize.

Since then, among many other awards, his historical novel The Englishman’s Boy and book Daddy Lenin and Other Stories have also won “The GG,” placing him in the company of the most-decorated authors in Canadian history.

He is one of only four authors to have taken the GG English fiction award three times. (The others are Alice Munro, Hugh MacLennan and Michael Ondaatje.)

No one has won it more often.

Also, The Englishman’s Boy was made into a television series, in which Vanderhaeghe had a cameo as a bartender. R.H. Thomson, by the way, is terrifying as the main villain. Watch it.

He has, of course, published other works including two plays and other historical novels including The Last Crossing, A Good Man, and the most recent August into Winter, which has one of the most horrifying villains in the history of literature. Read it.

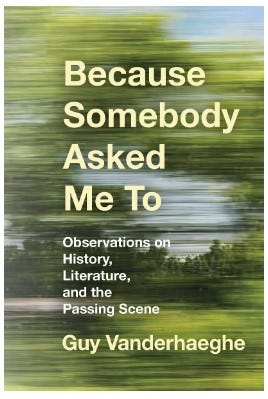

Then in late September came the launch of Because Somebody Asked Me To: Observations on History, Literature, and the Passing Scene, published by Saskatoon’s Thistledown Press.

In his own words, the book is something of a “hodgepodge” and the closest thing to a memoir he will likely ever write. Reviews of other great authors mingle with observations of history, tales from his past, and a must-read story about how Man Descending was accepted by Macmillan of Canada.

Most interesting, perhaps, to the authorial community is, as the bookstore put it, an examination of “how the Canadian literary scene has shifted during the course of his career — the economic, societal, and cultural changes that have made the old world of writing and publishing scarcely recognizable.”

I asked him to expand on that, and his first comment, I must say, surprised me somewhat. As a journalist of more than 30 years, and an author of about eight years, I saw my worlds slam together.

“I think the biggest change has been the demise of newspapers,” Vanderhaeghe said.

“When I started writing, every newspaper in Canada in a city of, say, over 100,000 people, I would guess, had a books page and a books page editor. They all reviewed books.

“I was an unknown writer, but I could get 25 or 30 reviews right across the country. For my first book I’m thinking St. John’s, Halifax, Moncton, St. John, Fredericton, . . . you could go across the country. Toronto — two Toronto papers. Et cetera, et cetera.

“So that was huge.

“And that kind of allowed for beginning writers to get a toehold. Now, it’s very, very tough to get a toehold, because where are you going to get it? The only place you can get it is Amazon. It’s the biggest market for books.

“If your book in some way doesn’t take off, it’s very hard for it to get a toehold and gain ground.”

In the “old days,” such massive online and chain bookstores did not exist as they do now.

At the time, he recalled, there were perhaps five or six independent bookstores in Saskatoon. Today, if your book doesn’t make a splash on the massive platforms of Amazon and/or Indigo, good luck.

The second big change has come in the publishing industry itself.

“When I started writing, there were a number of independent, relatively independent, Canadian branch plants of American and British publishers. McClelland and Stewart was an independent, Macmillan of Canada was an independent.

“Now, it’s Penguin Random House. That’s basically it. And all of their imprints – Random Penguin, Doubleday, Knopf – they’re all under one big corporate thing. That’s not good.

“So, you have this huge publisher and below it there are a number of smaller, literary, often regional publishers, who subsist basically on government grants to keep running.”

Publishing opportunities today for younger writers, therefore, have substantially reduced. Many, instead, are self-publishing or online publishing.

“You might argue that fills the gap, but I don’t think it does,” Vanderhaeghe told me. “The editing services which I think are important for writing, they disappear.

“I’m glad that I started when I started.”

He had much more to say, at my prompting, but most of his observations can be found in the new collection.

“It is a grab bag book. I can’t pretend that it isn’t.

“But there are two obsessions that the book reflects in one way or another: what is the meaning of history, and what is the meaning of literature. Do they ever coincide, and what happens when they sometimes collide?”

Fascinating and educational post, Jo. I hadn’t heard of this author, but now am inclined to check him out. His comments on the publishing industry strike true and are a bit depressing. Thanks for sharing your interview with us!

I read Man Descending back in the 80s. It's an exceptional book by an exceptional writer